Written by Adam Heath

Photos courtesy of Matt Bassett and Carol Battram

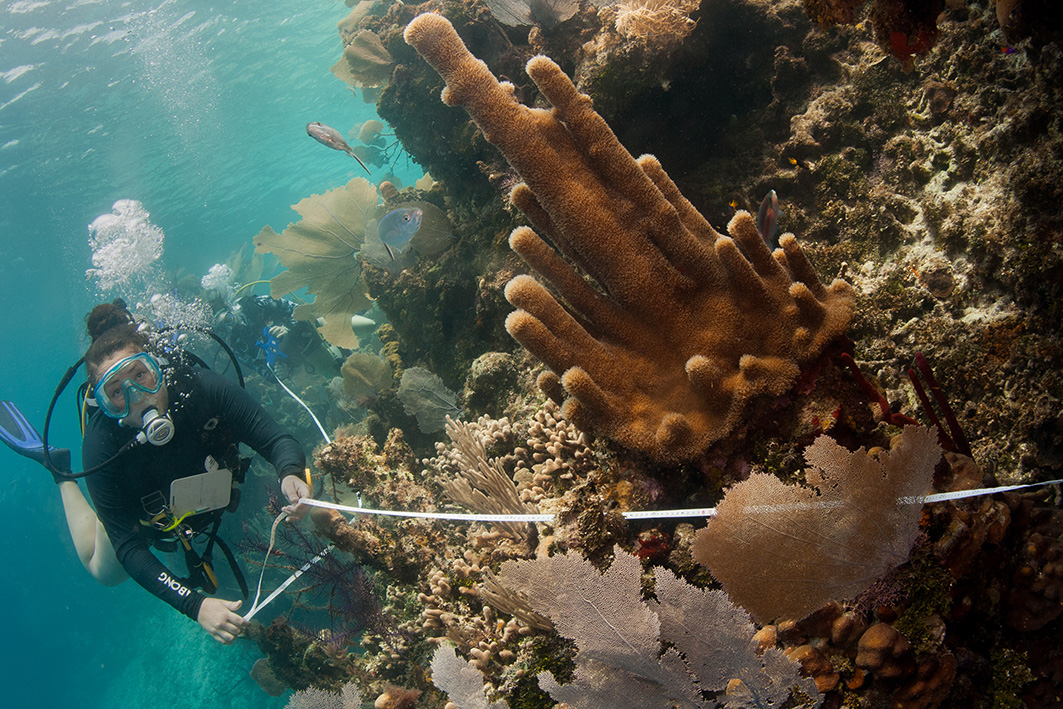

During the summer of 2017 I spent 6 weeks with Opwall in Honduras splitting my time equally between their two marine sites: one near the town of Tela on the mainland and the other on the island of Utila. As a Research Assistant I was involved in all the projects going on, including 3D modelling, lionfish ecology and benthic transects. One subject really caught my attention: the plight of the long-spined sea urchin. Sea urchins may not be the first thing to come to mind when you think of a coral reef, and at a glance they don’t appear particularly cute. But beneath those prickly spines hides a surprising amount of personality and perhaps the key to saving Caribbean reefs.

Urchin was the old English word for hedgehog, and the long-spined sea urchin, which we affectionately called Diadema (from its scientific name Diadema antillarum) can be just as enchanting as England’s favourite spiky mammal. The most heartwarming moment of my trip came after an early morning dive in Tela, as we walked back up the beach looking forward to breakfast. Some of the local kids took an interest in the red bucket of urchins we had collected. I remember Max (our site manager and a really nice guy) helping them gingerly hold a medium sized urchin that had four inch spines projecting from a body about the size of a golf ball. It was clear from their delighted giggles that they were enamoured with the odd creature, Max’s bubbling enthusiasm clearly rubbing off despite the language barrier. Holding one in your hand is an unusual experience, as dozens of their hydraulic tube feet act like little suction cups to pull the urchin across your palm- and they move surprisingly fast.

Diadema have an amazing amount of movement in their spines which are much more mobile than the relatively passive spikes of a hedgehog or porcupine. If you ever have the privilege to come across one delicately tickle the side of one of its longer spines and you’ll see the nearby spines react and dance around your finger. This is because they have a layer of skin and muscle tissue surrounding their white calcium carbonate shell or ‘test’. The function of the outer layer was illustrated on a dive looking for lionfish with Mitch (one of the dive masters). He and I found the remains of an urchin which had just been eaten, probably by a spiny lobster. The test was cracked open and the insides removed, but the outer tissues around the test and the spines was still intact, and behaved just like a living urchin, seemingly unaware that it’s internal organs were missing.

Like hedgehogs, Diadema spend a lot of the day hiding, and use crevices among the coral and cracks in the rocks to hide from predators. Unlike hedgehogs though, which are omnivorous and eat slugs, worms and insects, Diadema are peaceful herbivores and primarily graze on the plant-like algae that grows on reefs. It is this ecological role which we think makes the Diadema so important, because modern Caribbean reefs are suffering from an algal takeover: imagine weeds taking over your entire garden.

So why are these urchins struggling? In 1983 Diadema sea urchins suffered a catastrophe, with over 97% of all Diadema dying throughout the whole Caribbean, and no other species has seemed to be able take up the role of stopping algal growth. We still don’t know for sure what caused the dieoff, although it was probably a disease spread from the Pacific. Nowadays you can only find Diadema in the shallows whereas before 1983 there were abundant numbers of Diadema in shallow and deep waters.

The only reef system we know of where Diadema has recovered in the deep is Banco Capiro, in Tela Bay, where I spent the first three weeks of my time in Honduras. This site is also the only reef with extremely high levels of coral cover and doesn’t have the same levels of algal overgrowth that plagues the rest of the Caribbean. We think it’s no coincidence that the place with the healthiest Diadema population also has the healthiest coral population. Perhaps if we can help Diadema in other parts of the Caribbean they can repay the favour by restoring the coral reefs to some of their former glory. Opwall is the only group that dives on this unique reef, and this gives Opwall the chance and responsibility to learn as much as we can about what makes this site and these urchins so special.

As one of the projects I got involved with in Tela, I helped Woody and Naomi (two students working on their respective final year projects for their undergraduate courses) run behavioural tests on adult and juvenile urchins in order to find out more about predator responses. We used the ubiquitous GoPro to film them as they reacted to a shadow passing overhead, specifically to record how much they waved their spines, and how this varied among individuals of different ages, sizes and in different amounts of cover. The only way to control the background light levels in the behavioural tests was to do the tests at night after the sun had set. This shouldn’t have been too much of an issue because in theory an experiment only had to run for around four minutes, and we only had to run six in an evening. Of course it wasn’t quite so simple! Their tube feet let them stick to walls but also allow a surprising turn of speed when you’d rather they’d just sit still so you can film them. Often by the time an urchin had finally settled in a crevice, or had stopped trying to climb the walls of the tank the temperature would have have dropped and we’d need to wait for it to heat up again.

Later in the season I moved to Opwall’s other site on the island of Utila, which is a typical Caribbean reef with very few Diadema and lots of algae. This was the benefit of staying for six weeks, I could split my time between the two sites and get a much more diverse experience.

In Utila, Natalie was running a project for her PhD to try and help Diadema recover in the deeper waters. Nat wanted to create new habitats for Diadema at around 15m depth on the reef just offshore from our main site. The idea was pretty simple, by increasing the number of places they could hide we hoped to mimic the favourable conditions found over in Tela, but it’s never as easy in practice. Groups of us Research assistants and Masters students would take turns helping Nat mix small batches of concrete under the hot Honduran sun to build small concrete caves which we’d then take down on dives and position throughout the reef. Unfortunately, the urchins didn’t seem to appreciate all the effort that was put into creating their little concrete homes and would neither colonise them, or even stay near when they were relocated to them.

Nat was also collecting genetic samples so she could compare the populations between Tela and Utila to see if there was some hidden factor that makes the Tela urchins special. A longer term plan involves developing ways to breed urchins in captivity. This is easier said than done however. Diadema actually have a long larval stage where they drift around in the open ocean, and mimicking these conditions has proved elusive as of yet. As you can tell, there is so much we still need to do and discover.

It may not sound like it, but I probably spent less than a third of my time helping with Diadema related projects! I could talk just as much about the lionfish invasion, but I’ll leave that for another time.

Social Media Links