Written by Kieran McCloskey

Photos Courtesy of Kieran McCloskey & Dan Exton

You would be surprised by how noisy the underwater environment really is. Whale songs and dolphin clicks are well known to the general public, but marine mammals are not the only creatures that are capable of producing and utilising underwater sound. As reef activity increases around dawn and dusk, a chorus of acoustic sounds can be heard from a variety aquatic organisms. If you listen closely, you’ll immediately notice the snaps of shrimp and the loud crunching by grazing fish and invertebrates. You might also hear the pops, chirps, grunts, and whoops of fish communicating with one another to establish territories, fend off intruders or potentially entice a mate. All of these sounds are put together to compose what is called a soundscape, an acoustic signature for a specific environment.

We now know that this orchestra of biological and non-biological sounds offers a wealth of information about the aquatic environment. Furthermore, organisms are capable of utilising this information for a variety of important biological functions, such as communication, navigation, reproduction, finding food and avoiding predators. Unfortunately, wildlife are not the only ones making noise in our oceans. Anthropogenic (or man-made) noise has become a universal characteristic among natural soundscapes, and is now considered a pollutant of global concern. Our research group at the University of Exeter has been investigating marine bioacoustics and the harmful impacts of noise pollution for over a decade. Our work has shown that anthropogenic noise affects many aspects of fish and invertebrate biology and ecology, including physiology, communication, behaviour, reproduction and survival.

If you’re reading this blog and wondering how you could have overlooked the wonderful world of underwater acoustics on your last SCUBA diving trip, you’re not the only one. The famous French explorer, Jacques Cousteau once referred to the ocean as ‘The Silent World’. The reason for this misconception can likely be attributed to the use of inherently noisy SCUBA diving equipment that would mask most sounds coming from the surrounding underwater environment. In fact, it is because of the noise from recreational SCUBA gear that the producers of the BBC’s successful Blue Planet II series chose to use sophisticated, but much quieter, rebreather equipment to enable up-close shots with the wildlife. In recent years, the influence of diver presence on fish behaviour and community assemblage has been investigated. However, this research was not able to tease apart whether the loud noise from recreational diving equipment contributed to the observed changes.

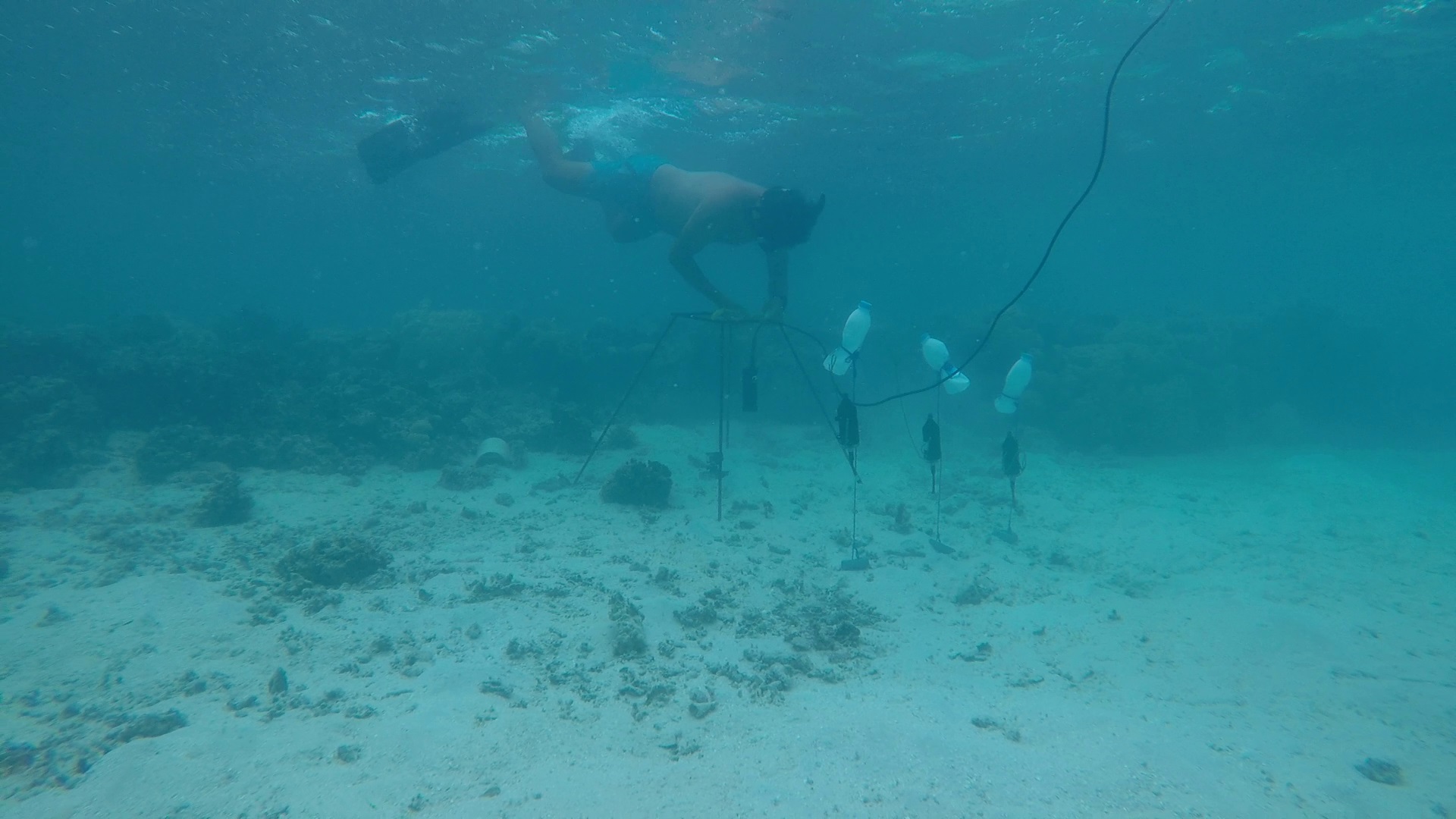

This is what I hope to explore this field season on the island of Utila, Honduras with Operation Wallacea. Building on my previous research on the impacts of noise on fish biology and behaviour, I intend to closely examine how SCUBA noise may be affecting important mutualistic interactions between Pederson’s cleaner shrimp (Ancylomenes pedersoni) and their clients among coral reef communities. Having led research on the Great Barrier Reef and in the coastal waters of the UK, I will be combining my expertise in bioacoustics with the experience and knowledge of the Operation Wallacea research staff to carry out this investigation. It’s worth noting that there are an estimated 6 million active SCUBA divers worldwide, and the potential for the widespread impacts of SCUBA noise on wildlife could be significant. Ultimately, this research will deepen our understanding of the effects of anthropogenic stressors on coral reef communities and will be vital to shaping safe and environmentally conscientious diving practice.

Social Media Links