Written by Darren O’Connell

Written by Darren O’Connell

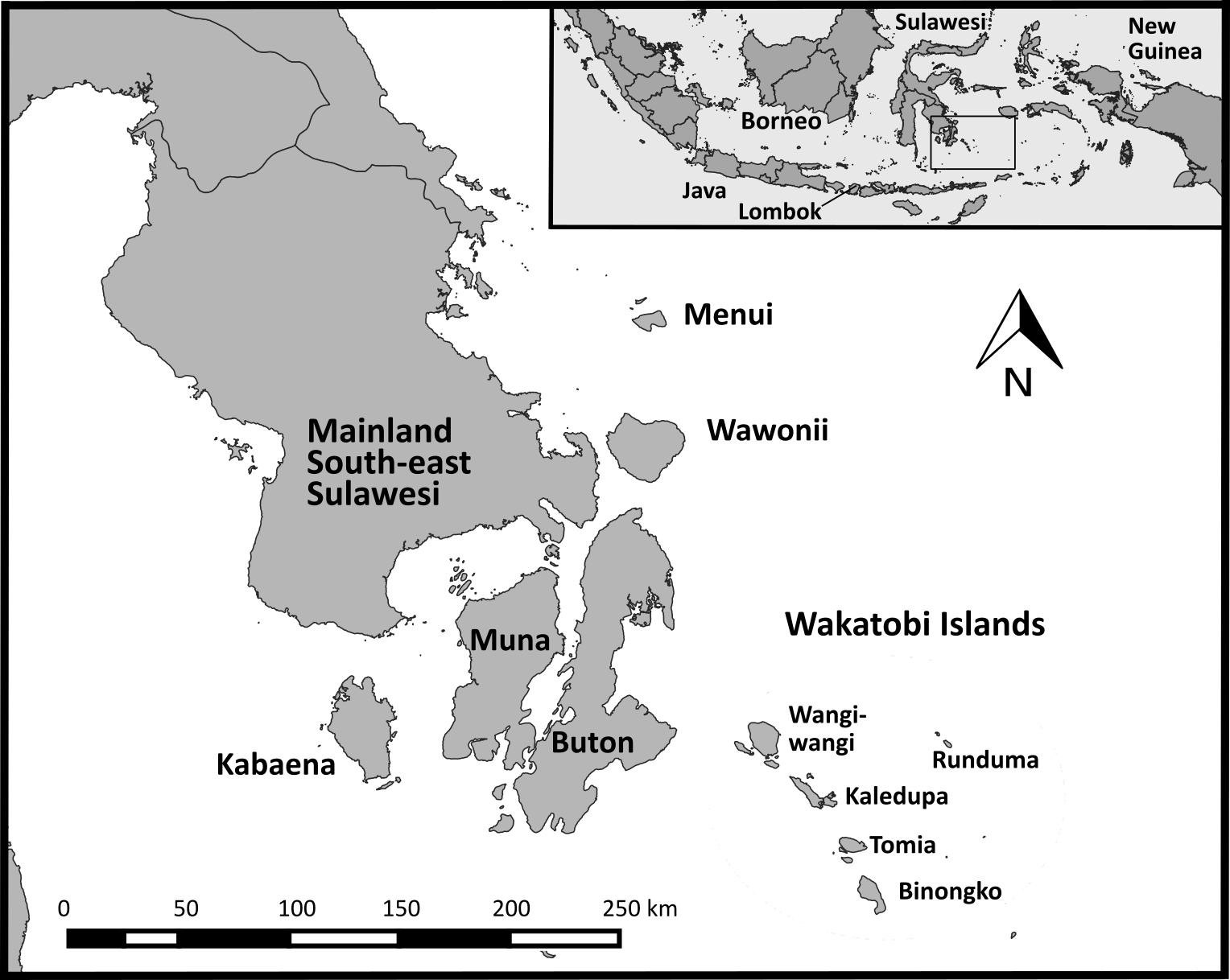

Almost as long as I can remember I’ve wanted to be a Zoologist. Growing up on a steady diet of Attenborough documents, I dreamed of exploring new lands, discovering weird and wonderful species. I wanted to be the next Darwin. The next Wallace. In a lot of ways my PhD research has been the fulfilment of that dream. It all started with my undergraduate thesis project in the Trinity College Dublin (TCD) Zoology Department. When Prof Nicola Marples and Dr David Kelly offered a project studying speciation on islands I jumped at it. I spent the summer before the final year of my undergraduate island hopping in south-east Sulawesi, Indonesia collecting data on how the physical traits of sunbird species had changed on isolated islands. Nicola and Dave’s project fieldwork was organised by Operation Wallacea, so we worked with Operation Wallacea staff as we moved around the islands and got to interact with scientists focusing on some of the other unique wildlife of Sulawesi.

Sulawesi is a region of massive interest to evolutionary biology. It is the intersection where Asian and Australian flora and fauna meet, and is separated by deep ocean trenches ensuring it has never been connected to a continent, allowing many unique species to develop there. As well as providing a fascinating study system, South-east Sulawesi has some incredible wildlife. Knobbed Hornbills, Tarsiers and Sulawesi Bear Cuscus are weird and wonderful treats. In particular working with the birds of this region was incredible, and I was adamant it wouldn’t end up being a once in a lifetime experience! As well as allowing me to follow my island hopping ambitions, this project kicked off what I predict will be a lifelong obsession. Having previously been a typical fan of large charismatic mammals, I became a full convert to the world of birds (it’s fundamentally all about the birds!).

Sulawesi is a region of massive interest to evolutionary biology. It is the intersection where Asian and Australian flora and fauna meet, and is separated by deep ocean trenches ensuring it has never been connected to a continent, allowing many unique species to develop there. As well as providing a fascinating study system, South-east Sulawesi has some incredible wildlife. Knobbed Hornbills, Tarsiers and Sulawesi Bear Cuscus are weird and wonderful treats. In particular working with the birds of this region was incredible, and I was adamant it wouldn’t end up being a once in a lifetime experience! As well as allowing me to follow my island hopping ambitions, this project kicked off what I predict will be a lifelong obsession. Having previously been a typical fan of large charismatic mammals, I became a full convert to the world of birds (it’s fundamentally all about the birds!).

After completing my undergraduate degree and working on a few other research projects I was lucky enough to secure funding from  Operation Wallacea and the Irish Research Council to return to South-east Sulawesi to work on the speciation of the birds in that region. My supervisors were convinced that some of the island bird populations were unrecognised unique species. I set out to investigate this and understand their evolution. Historically most species have been described using physical traits, known as the phenotypic species concept. Modern genetics techniques have shown that we had vastly underestimated species diversity, with many species which seemed superficially similar to other species being proven to have separated genetically. However deciding where to draw the line on how genetically separate a population needs to be to be called a species can be arbitrary and knowledge on this subject is still developing. Therefore modern avian taxonomy requires that you demonstrate differences in genetics, physical traits, and song to show a population is a separate species. The difference in song is particularly important as this is how birds find their mates, so if populations are singing differently they won’t breed and so stay separate.

Operation Wallacea and the Irish Research Council to return to South-east Sulawesi to work on the speciation of the birds in that region. My supervisors were convinced that some of the island bird populations were unrecognised unique species. I set out to investigate this and understand their evolution. Historically most species have been described using physical traits, known as the phenotypic species concept. Modern genetics techniques have shown that we had vastly underestimated species diversity, with many species which seemed superficially similar to other species being proven to have separated genetically. However deciding where to draw the line on how genetically separate a population needs to be to be called a species can be arbitrary and knowledge on this subject is still developing. Therefore modern avian taxonomy requires that you demonstrate differences in genetics, physical traits, and song to show a population is a separate species. The difference in song is particularly important as this is how birds find their mates, so if populations are singing differently they won’t breed and so stay separate.

My PhD field work involved travelling around beautiful tropical islands in remote parts of Indonesia. Tough work, but someone has to do it! We moved site every week as part of our sampling regime, working in mountain areas, swamps and everything in between. We stayed with local families, sometimes in hovels, sometimes in veritable palaces, often with one following the other. The hospitality we were treated with was always incredible. Equally incredible was what we found during our research trips. The bird populations of the region, particularly on the isolated Wakatobi Islands, showed much unappreciated biodiversity with unrecognised subspecies and full species as well as unique biogeographic patterns in the island populations. One of the new species we discovered, the Wangi-wangi White-eye, is particularly novel, being found on only one small (155km2) islands >3000km away from its closest relative. This species needs urgent conservation action, as its entire population may be less than 200 breeding pairs. Studying speciation South-east Sulawesi meant we travelled to a number of islands which had received little or no scientific attention in the past, letting us add much to the knowledge of the distribution of birds and mammals in the region.

My PhD field work involved travelling around beautiful tropical islands in remote parts of Indonesia. Tough work, but someone has to do it! We moved site every week as part of our sampling regime, working in mountain areas, swamps and everything in between. We stayed with local families, sometimes in hovels, sometimes in veritable palaces, often with one following the other. The hospitality we were treated with was always incredible. Equally incredible was what we found during our research trips. The bird populations of the region, particularly on the isolated Wakatobi Islands, showed much unappreciated biodiversity with unrecognised subspecies and full species as well as unique biogeographic patterns in the island populations. One of the new species we discovered, the Wangi-wangi White-eye, is particularly novel, being found on only one small (155km2) islands >3000km away from its closest relative. This species needs urgent conservation action, as its entire population may be less than 200 breeding pairs. Studying speciation South-east Sulawesi meant we travelled to a number of islands which had received little or no scientific attention in the past, letting us add much to the knowledge of the distribution of birds and mammals in the region.

Wakatobi White-eye

Wangi-wangi White-eye

As well as the excitement of exploring islands new to science and finding new bird species, these discoveries may have important implications for the conservation of biodiversity in Sulawesi! As resources for conservation are always limited conservation organisations prioritise their funding for designated areas which are home to the most unique and rare species. One such designation is the BirdLife International Endemic Bird Areas. In order to be recognised as an Endemic Bird Area, a region needs to be home to two species entirely restricted to that area. The recognition of two new bird species for the Wakatobi Islands (Wakatobi White-eye and Wangi-wangi White-eye), should make a strong case that the Wakatobi Islands be recognised as an Endemic Bird Area and receive greater support from BirdLife International for conservation efforts on the islands. The Wakatobi Islands have experienced a massive increase in human population, so all habitats on the islands have been badly damaged. Urgent action is needed to protect the remaining habitats on these islands to protect the Wakatobi’s unique bird species. Doing so will also have knock-on benefits for other species found on the islands, such as the Critically Endangered Yellow-crested Cockatoo (Cacatua sulphurea). We hope that our work will help highlight the biodiversity of the Wakatobi Islands and wider Sulawesi region, and ensure it is protected as the world faces a looming extinction crisis. TCD, Operation Wallacea and our collaborators in Halu Oleo University are determined to continue to work hard to ensure that some of the stunning wild areas of this region remain intact, and its unique species are recognised!

Darren O’Connell

Darren’s full PhD thesis is available here

Acknowledgements

Thanks to TCD, Halu Oleo University and Operation Wallacea for facilitating, planning and providing logistical support for this research. A big thanks to Kementerian Riset Teknologi Dan Pendidikan Tinggi (RISTEKDIKTI) for providing the necessary permits and approvals for this study (0143/SlP/FRP/SM/Vll/2010, 278/SlP/FRP/SM/Vll/2012, 279/SIP/FRP/SM/VIII/2012, 174/SIP/FRP/E5/Dit.KI/V/2016, 159/SIP/FRP/E5/Fit.KIVII/2017 and 160/SIP/FRP/E5/Fit.KIVII/2017). This research would not have been possible without my supervisors Prof Nicola Marples and Dr David Kelly and my collaborators Prof Kangkuso Analuddin and Adi Karya. Finally, we like to thank all of the research assistants who contributed across many field seasons, particularly Síofra Sealy, Nur Fajrhi, Naomi Lawless, Alex Delamer and Sulaiman La Ode.

About the author

Darren O’Connell recently completed a PhD in The Marples Lab in the Department of Zoology, Trinity College Dublin, partially supported by Operation Wallacea. For his PhD, Darren studied bird evolution and island biogeography in Sulawesi, Indonesia, supported by the Irish Research Council. Darren has just joined the Laboratory of Molecular Evolution and Mammalian Phylogenetics in the School of Biology and Environmental Science, University College Dublin and will be using molecular tools to understand how environmental stressors influence aging in wild bats.

Research generated related to Darren’s PhD:

O’Connell, D.P., Kelly, D.J., Lawless, N., O’Brien, K., Ó Marcaigh, F., Karya, A., Analuddin, K. and Marples, N.M. (2019) A sympatric pair of undescribed white-eye species (Aves: Zosteropidae: Zosterops) with different origins. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. XX: 1-24.

View the paper here

Read the blog here

O’Connell, D.P., Kelly, D.J., Kelly, S.B.A., Sealy, S., Karya, A., Analuddin, K. and Marples, N.M. (2019) Increased sexual dimorphism in dense populations of Olive-backed Sunbirds on small islands: morphological niche contraction in females but not males. Emu – Austral Ornithology, Special Issue on “Ornithological advances in New Guinea and the Indo-Pacific”.

View the paper here

Read the blog here

O’Connell, D.P., Kelly, D.J., Lawless, N., Karya, A., Analuddin, K. and Marples, N.M. (2019) Diversification of a ‘great speciator’ in the Wallacea region: differing responses of closely related resident and migratory kingfisher species (Aves: Alcedinidae: Todiramphus). Ibis.

View the paper here

Read the blog here

Martin, T.E., Monkhouse, J., O’Connell, D.P., Analuddin, K., Karya, A., Priston, N.E.C., Palmer, C.A., Harrison, B., Baddams, J., Mustari, A.H., Wheeler, P.M. and Tosh, D.G. (2019) Distribution and status of threatened and endemic marsupials on the offshore islands of south-east Sulawesi, Indonesia. Australian Mammalogy, 41: 76-81.

View the paper here

Read the blog here

Monkhouse, J., O’Connell, D.P., Karya, A., Analuddin, K., Kelly, D.J., Marples, N.M. and Martin, T.E. (in press) The avifauna of Menui Island, south-east Sulawesi, Indonesia. Forktail.

Martin, T.E., O’Connell, D.P., Kelly, D.J., Karya, A., Analuddin, K. and Nicola Marples (2018) Range extension for Dwarf Sparrowhawk (Accipiter nanus) in South-east Sulawesi – is it really restricted to upland forests? BirdingASIA. 29: 103-104.

View the paper here

Read the blog here

O’Connell, D.P., Sealy, S., Ó Marcaigh, F., Karya , A., Bahrun, A., Analuddin, K., Kelly, D.J. and Marples, N.M. (2017) The avifauna of Kabaena Island, South-east Sulawesi, Indonesia. Forktail, 33: 40-45.

View the paper here

Read the blog here

Social Media Links